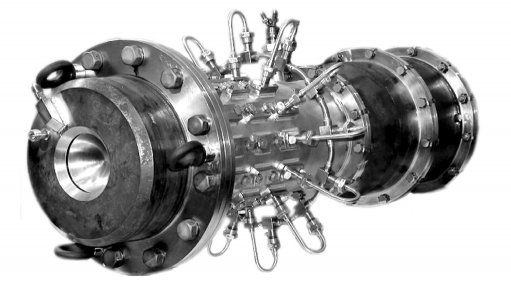

The pulse-detonation technology demonstration engine

Photo by: Rostec

Russia’s State-owned Rostec group has announced that its subsidiary, United Engine Corporation (UEC), had completed the first round of tests on a pulse-detonation technology demonstrator engine. The engine is being developed by UEC’s Lyulka design bureau and the project was launched in 2016.

“The first stage of testing the pulse-detonation engine demonstrator has been successfully completed,” reported the Rostec aviation cluster in its statement. “It has shown the required performance characteristics. In some operation modes, the specific thrust was up to 50% higher than the performance of traditional power plants. This will prospectively increase the maximum range and payload mass of aircraft by 1.3-1.5 times.”

Pulse-detonation engines are the supersonic counterparts to subsonic pulse jets, the latter being best known for being used as the engines for the German Fieseler Fi-103 cruise missile (much better known as the V1) during the Second World War. Both types of engine employ relatively few mechanical moving parts.

In theory, both types are more efficient than conventional jet engines, but in practice there are significant problems with them. For example, with the V1, the missile needed to have accumulated airspeed before its pulse jet could function – which is why it had to be launched from a catapult ramp or dropped from an aircraft. The difficulties with pulse-detonation engines are much greater.

In pulse-detonation engines, combustion takes place in a shaft so constructed (including valves at its extremities) that gas (including air) can pass through it in only one direction. To simplify, the fuel and oxidiser mix is combusted in the tube in such a way that it expands at supersonic speed and sends a shock (detonation) wave down the shaft or tube and out through a nozzle at the end, producing thrust. This process creates a vacuum in the tube, which causes valves at its front to open and admit air (or other oxidiser) and permit the process to be repeated. Simple in theory, decidedly difficult in practice. (A pulse jet works the same way, only the shock wave is subsonic, making it easier to achieve and sustain, and is called a deflagration wave.)

But, if achieved, pulse-detonation engines would provide aircraft with improved flight dynamics and manoeuvrability. They could also be used to power other types of craft as well. “The design will be able to be applied, for example, on orbital spaceplanes, supersonic and hypersonic aircraft, and future-generation rocket and space systems,” pointed out the Rostec aviation cluster.

“The simplicity of the design and its relatively low requirements for gas-dynamic process values allow us to integrate solutions developed on previous engine generations,” noted Lyulka design bureau general design director Evgeny Marchukov. “This provides a great commercial and economic advantage in comparison with the more traditional engines that are currently under development.”