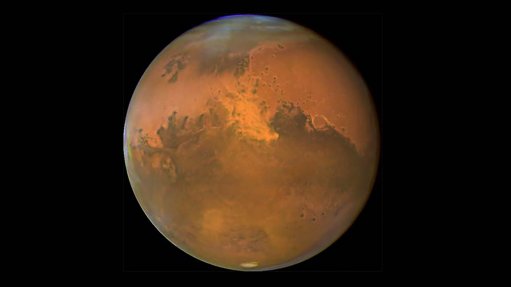

Mars

Photo by: Nasa

Seismologists from Rice University in Houston in the US state of Texas have for the first time been able to directly measure the boundaries between the different levels that compose the planet Mars – the crust, the mantle and the core – plus a very important transition zone within the mantle. They did so by using data from the InSight lander. Previously, the depth of these boundaries had been estimated using various models.

InSight is an international mission headed by the US National Aeronautics and Space Agency which touched down in the Elysium Planitia region of the Red Planet in November 2018. InSight is an acronym for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport. The lander deployed a seismometer developed by a European-American team led by France’s National Centre of Space Studies (better known as CNES).

InSight was sent to Mars specifically to collect data on that planet’s internal structure. A seismometer measures energy waves that are triggered by underground events such as the breaking of rock, movement along faults, volcanic events, explosions as well as by events like meteorite impacts.

“The traditional way to investigate structures beneath Earth is to analyse earthquake signals using dense networks of seismic stations.” explained Rice University graduate student and study co-author Sizhuang Deng. “Mars is much less tectonically active, which means it will have far fewer marsquake events compared with Earth. Moreover, with only one seismic station on Mars, we cannot employ methods that rely on seismic networks.”

Instead, the researchers analysed data, provided by more than 170 marsquakes detected by the seismometer from February to September last year, using a method known as ambient noise autocorrelation. “It uses continuous noise data recorded by the single seismic station on Mars to extract pronounced reflection signals from seismic boundaries,” he elucidated.

By this means, Deng and study co-author Rice University Carey Croneis Professor of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences Alan Levander determined that the boundary between the Martian crust and mantle lay 35 km beneath InSight. Within the mantle, there is a zone where magnesium iron silicates are subject to geochemical change caused by heat and pressure. Above this zone, magnesium iron silicates form a mineral called olivine and below it they are in the form of another mineral, wadsleyite. The zone is called the olivine-wadsleyite transition and it was measured to be from 1 110 km to 1 170 km beneath the lander. Finally, the boundary between the mantle and the core was found to be 1 520 km to 1 600 km underneath the spacecraft.

“The temperature at the olivine-wadsleyite transition is an important key to building thermal models of Mars,” pointed out Deng. “From the depth of the transition, we can easily calculate the pressure, and with that, we can derive the temperature.”

“In the absence of plate tectonics on Mars, its early history is mostly preserved compared with Earth,” he highlighted. “The depth estimates of Martian seismic boundaries can provide indications to better understand its past as well as the formation and evolution of terrestrial planets in general.”