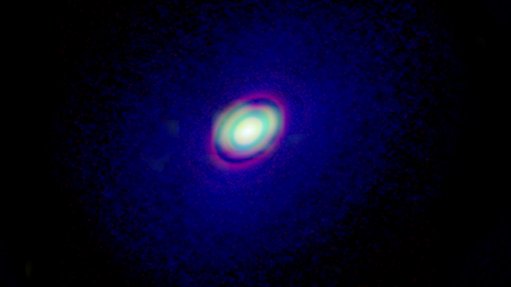

A composite image of HD 163296 and its encircling protoplanetary disc. The inner red regions show the dust in the disc, the inner green region represents the rare 13C17O, while the larger blue region shows the CO gas in the disc

Photo by: University of Leeds

Another major southern hemisphere radio telescope array, the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA), located in Chile, has proven essential in the making of another major astronomical discovery announced this week. The publishing of the new breakthrough (in the Astrophysical Journal Letters) came only a little more than 24 hours after the announcement of the discovery of gigantic radiowave-emitting “bubbles” in the centre of our galaxy, by researchers using South Africa’s MeerKAT radio telescope array.

Again, an international team of scientists was involved, led by UK Leeds University PhD researcher Alice Booth. They were studying the protoplanetary disc of gas and dust around a young star designated HD 163296 (it is in a protoplanetary disc that new planets form), which formed during the last six-million years. It lies 330 light years from Earth.

ALMA detected a very faint signal which revealed that the disc contained a rare form of carbon monoxide, called an isotopologue. This has the chemical formula of 13C17O (normal carbon monoxide has the chemical formula of CO), and has more mass that normal CO. As a result, the team was able to measure the mass of the disc with unprecedented accuracy.

“Our new observations showed there was between two and six times more mass hiding in the disc than previous observations could measure,” reported Booth. “This is an important finding in terms of the birth of planetary systems in discs – if they contain more gas, then they have more building material to form more massive planets.”

Recent observations of protoplanetary discs had puzzled astronomers because they did not appear to possess enough gas and dust to create the observed planets (known as exoplanets, because they are outside our solar system). “The disc-exoplanet mass discrepancy raises serious questions about how and when planets were formed,” explained Leeds University researcher and team member Dr John Ilee. “However, if other discs are hiding similar amounts of mass as HD 163296, then we may just have underestimated their masses until now.”

“We suspect that ALMA will allow us to observe this rare form of CO in many others discs,” pointed out Booth. “By doing that, we can more accurately measure their mass, and determine whether scientists have been underestimating how much matter they contain.”

ALMA is composed of 66 dishes and is an international project. It is, Booth noted, making an “amazing contribution … to our understanding of the Universe”.