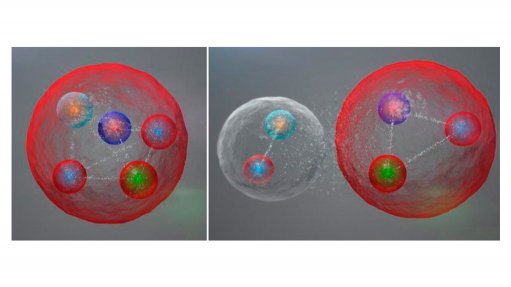

A pentaquark may be composed of five tightly bound quarks (illustrated left) or organised into a baryon (with three quarks) and a meson (one quark and one anti-quark) which are weakly bound together

Photo by: Daniel Dominguez/Cern

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) of the European Organisation for Nuclear Research (much better known as Cern), the world’s most powerful particle accelerator, has scored another major success with the discovery of a new class of exotic subatomic particles known as pentaquarks. The discovery was announced on Tuesday.

The pentaquark was found by the LHCb experiment, one of the six experiments in the LHC. (LHCb is the abbreviation for Large Hadron Collider beauty, which was originally focused on a particle known as a b quark or beauty quark.) The LHCb is a major and very sophisticated machine in its own right, being 21 m long, 13 m wide and 10 m high and weighing 5 600 t.

Back in 1964, US physicist Murray Gell-Mann theorised that baryons (a category of particle which includes protons and neutrons) and mesons were made up of even smaller particles, called quarks or anti-quarks. There are six different types of quarks (designated up, down, top, bottom, strange and charmed), each with its equivalent anti-quark.

“The pentaquark is not just any new particle,” explained LHCb spokesman Guy Wilkinson. “It represents a way to aggregate quarks, namely the fundamental constituents of ordinary protons and neutrons, in a pattern that has never been observed before in over fifty years of experimental searches. Studying its properties may allow us to understand better how ordinary matter, the protons and neutrons from which we’re all made, is constituted.”

“Benefiting from the large data set provided by the LHC and the excellent precision of our detector, we have examined all possibilities for these signals [detected by the LHCb] and conclude that they can only be explained by pentaquark states,” stated LHCb team member and Syracuse University physicist Tomasz Skwarnicki. “More precisely the states must be formed of two up quarks, one down quark, one charm quark and one anti-charm quark.”

The next step in the research will be to ascertain how the quarks are organised within the pentaquark. “The quarks could be tightly bound or they could be loosely bound in a sort of meson-baryon molecule, in which the meson and baryon feel a residual strong force similar to the one binding protons and neutrons to form [atomic] nuclei,” suggested LHCb and Tsinghua University physicist Liming Zhang.