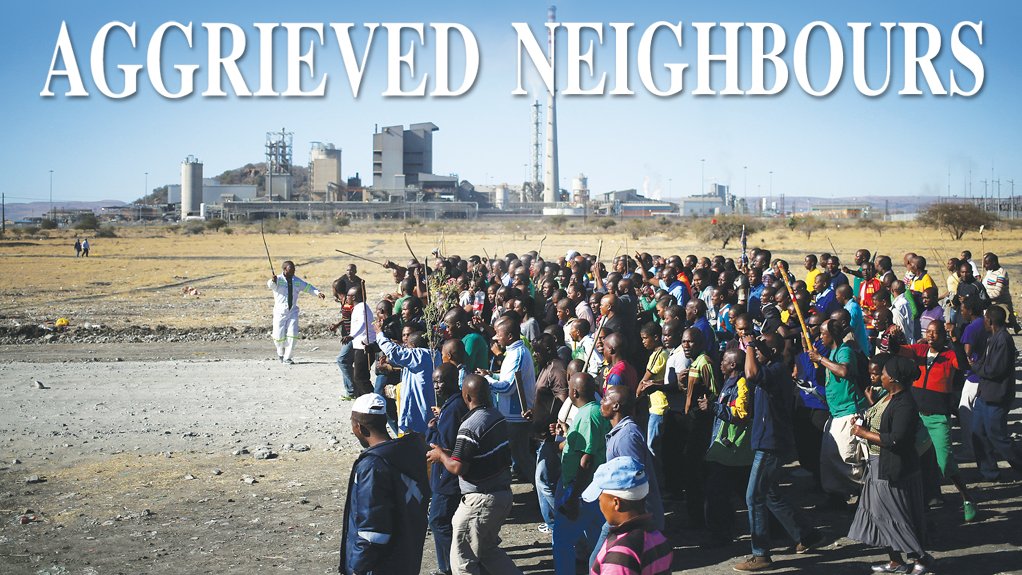

Perceptions mines are not doing enough for nearby communities fuelling protests

UP IN ARMS Community residents are seemingly more prone to airing grievances against mining companies using violent means

Photo by Reuters

NATURE VS NURTURE Whereas community protests against mining in developed countries tend to be focused on environmental harm, protests in South Africa tend to be about societal ills

Photo by Reuters

JOHANNESBURG (miningweekly.com) – In developed countries, community- based protest action (as opposed to industrial action) against mining companies is primarily related to environmental concerns. In South Africa, community-based protests against mining companies are rooted in socioeconomic issues, such as job creation, and infrastructure development.

“There is no doubt that increasing numbers of mining communities are protesting against mining activity in South Africa,” says Bench Marks Foundation lead researcher David van Wyk.

He says the national police commissioner recently revealed that about 14 740 crowd-related incidents take place in South Africa yearly. “Of that number, our estimates are that about 35 protests take place in mining communities every month. This means 2.8% of the service delivery protests are mining-related.”

Van Wyk adds that, given the thousands of municipalities and the comparatively small number of mining companies in South Africa, “2.8% is a high percentage and an indication of the level of dissatisfaction”.

However, Institute for Security Studies (ISS) crime and justice information hub manager Lizette Lancaster notes that the ISS Protest and Public Violence monitoring system does not expressly focus on mining-related incidents and, thus, she adds, it cannot be affirmed that incidents against mining companies are increasing.

Nonetheless, the monitor did record 39 such incidents from June 2013 to June 2018. Lancaster notes that almost half the incidents (16) were related to unemployment and demands for jobs. About six were related to communities’ perceptions that mines had neglected their social and labour plan (SLP) commitments or that there had been a lack of infrastructure development. Five were related to safety and environmental concerns, while the remaining 12 were either in support of industrial action, or about corruption, land ownership and use, mine ownership and illegal mining.

CAUSE FOR CONCERN

Some of the notable incidents recorded included Burgersfort residents, in Limpopo, burning tyres and blocking off roads in November 2014 and February 2015, demanding jobs, and security officers at the Lydenburg Chromex Mining operation, in Mpumalanga, using rubber bullets to disperse a group of angry residents, in November 2014, who had barricaded the mine access road, protesting the company’s failure to develop the area.

Lancaster notes that six people were arrested in July 2015 after a truck was torched during a protest in Majakaneng, near Brits, in the North West province, when a group of young men allegedly demanded that a local mine employ them. Later that year, in the same province, disgruntled youth from Morogong, Bojating, Phalane and Phadi demanded jobs on the mines at a protest in Ramokokastad, during which an office was burnt down.

In January 2016, youth from the Lesetlheng village, near Rustenburg, barricaded the road leading to the Sedibelo platinum mine, accusing it of not hiring locals. In May that year, Atok Mine management and Apel communities, in Limpopo, met to try to reach an amicable solution after protesters set several of the mine’s properties alight. In that same month, a stand-off ensued between Pilanesberg Platinum mineworkers and local community members over jobs, notes Lancaster.

In September 2016, residents from Ga-Malukane and Chaba Village blocked off the road at Witvinger that leads to Anglo American’s Mogalakwena platinum mine, in Limpopo, and set a truck alight, allegedly over unresolved mine promises. A year later, police requested that motorists find alternative routes after residents of Braakfontein informal settlement protested on the R104 road between Mooinooi and the Hartbeespoort dam, in the North West province, over a mine not employing locals.

Lancaster acknowledges that the 39 cases may not demonstrate the extent of the phenomenon, because “we capture instances of protest as reported in the media . . . so coverage is often uneven”.

Most recently, in June, nine residents of Ga-Pila were arrested for demanding to meet with the Mogalakwena mine CEO and, later that same month, residents of Dingleton, in the Northern Cape, accused Kumba Iron Ore of demolishing houses without proper authorisation and consultation. “There were running clashes between mine security, police and the community, which accused Kumba of using rubber bullets and violence to dispossess the legal inhabitants of Dingleton, in Kathu,” states Van Wyk.

At least one mining company is acutely aware of a seeming increase in community dissent. In April, Anglo American Platinum (Amplats) told Reuters that the platinum belt had experienced about 400 social unrest incidents between June 2016 and March 2018. Earlier that month, six workers were burnt to death when a mine-operated bus was petrol-bombed near its operations in Limpopo. Amplats added that, apart from the bus incident, there were at least 55 other recorded acts of violence.

Later that month, Mining Weekly reported that Anglo American Thermal Coal South Africa CEO July Ndlovu warned delegates at the 2018 Coalsafe conference, held in April, that the industry had to deal with community uprisings or “risk facing another Marikana”.

At the time, Ndlovu noted that, in the three months preceeding the conference, five Thermal Coal employees were threatened by community members while on their way to work. He also cited increased stoppages throughout the local mining industry because of “organised, well-resourced community protests”.

REASONS AND SOLUTIONS

Lancaster says the reasons for the seeming rise in violent mine-related protests are very complex, as “more communities are fighting to gain agency and a voice to be heard not only by government but all organisations they perceive to wield power in their area”.

She notes that, as with most protests, communities are protesting against inequality in terms of rights and economic power, adding that it is a struggle to gain the socioeconomic rights promised and protected by the Constitution.

Ndlovu believes that this perceived inequality leads to frustration, which has resulted in a disenfranchised public that the mining industry is ill-equipped to deal with.

Van Wyk adds that, “quite simply”, the communities, being aggrieved with mining companies, want to take their grievances directly to the companies, rather than complicate matters further with an unnecessary approach to government entities.

“Currently, relations between communities and mining companies are very poor and are [becoming] progressively poorer. The biggest problem is that mining companies make promises to communities that they don’t keep,” he states, citing the general lack of job creation and the disjointed implementation of SLPs.

While recognising that mining companies are ultimately businesses with obligations to shareholders, Van Wyk stresses that neglecting or delaying social investment results only in “angry and disillusioned communities protesting and causing havoc on their doorsteps”.

Lancaster adds that mining houses need to see the surrounding communities as part of their ‘constituencies’. “While many mining houses have extensive community development and outreach programmes, communities are increasingly voicing their dissatisfaction with a lack of socioeconomic transformation and upliftment not only because of the failure of big business but also [the failure of] the State.”

She suggests that strong community leadership, as well as improved local government service delivery and dialogue between the mines and the communities, will lead to some progress and the de-escalation of protests.

Meanwhile, Van Wyk notes that the Bench Marks Foundation has put forward some proposals to improve the relationship between communities and mining companies, such as an Independent Capacity-Building Fund (ICF), paid for by the industry and government.

“The ICF will not only facilitate informed decision-making by communities but will also address skewed power relations, allowing for a more level playing field and increasing developmental capacity, thereby leading to better developmental outcomes, improved relations and dialogue.”

Additionally, the foundation suggests that an independent problem-solving facility, geared towards sustainable solutions, is urgently needed in the mining sector to address the prevailing problems between mining-impacted communities and mining companies.

“The seriousness and highly problematic nature of this situation cannot be underestimated. In response to this situation, Bench Marks has developed an Independent Problem Solving Service (IPSS) for the sector,” explains Van Wyk.

The IPSS is underpinned by social justice values and is the result of many years of consultation and research. The foundation has been engaging with a wide range of civil society organisations, including the Centre for Applied Legal Studies, Action Aid and hundreds of communities that have endorsed this approach.

“We are also engaging mining companies and Minerals Council South Africa, and . . . we have also called for this to be included in the Mining Charter.”

Ultimately, it is the State’s inability to address unemployment and inequality that has led to increased levels of frustration and dissatisfaction, which have, rightly or wrongly, been projected onto mining companies. Nonetheless, mining companies are not entirely blameless, and more effort is required, specifically with regard to the planning, integration and implementation of SLPs.

Comments

Press Office

Announcements

What's On

Subscribe to improve your user experience...

Option 1 (equivalent of R125 a month):

Receive a weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine

(print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

Receive daily email newsletters

Access to full search results

Access archive of magazine back copies

Access to Projects in Progress

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

Option 2 (equivalent of R375 a month):

All benefits from Option 1

PLUS

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports, in PDF format, on various industrial and mining sectors

including Electricity; Water; Energy Transition; Hydrogen; Roads, Rail and Ports; Coal; Gold; Platinum; Battery Metals; etc.

Already a subscriber?

Forgotten your password?

Receive weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine (print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

➕

Recieve daily email newsletters

➕

Access to full search results

➕

Access archive of magazine back copies

➕

Access to Projects in Progress

➕

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

RESEARCH CHANNEL AFRICA

R4500 (equivalent of R375 a month)

SUBSCRIBEAll benefits from Option 1

➕

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports on various industrial and mining sectors, in PDF format, including on:

Electricity

➕

Water

➕

Energy Transition

➕

Hydrogen

➕

Roads, Rail and Ports

➕

Coal

➕

Gold

➕

Platinum

➕

Battery Metals

➕

etc.

Receive all benefits from Option 1 or Option 2 delivered to numerous people at your company

➕

Multiple User names and Passwords for simultaneous log-ins

➕

Intranet integration access to all in your organisation